It’s always controversial; it’s always over-the-top; it’s always messy; it’s always astounding; and it’s always tiring, challenging and frustrating, especially when you’re asking yourself. What is the point? Or Is this really art? For me, however, the Venice Biennale is never disappointing — until last year’s.

Overly stocked with video art, I found myself desperately in search of work that embodied any of the above adjectives. The films were too long or too short or boring or annoying or downright offensive (not that the word offensive isn’t oftentimes used in reaction to work at the biennales). A notable exception was the Canadian entry, One Day in the Life of Noah Plugattuk, a movie by Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk that described the true story of an attempt by the Canadian government to relocate his people during the 1950s.

The Ghanaians exhibited for the first time and their space, created by Sir David Adjaye (who also designed the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture), stood out. El-Anatsui’s work dominated with his hundreds of thousands of found objects woven into massive curtains (images below). Talk about sustainable art!

And I also thought The Netherlands did a great job of honoring modernism’s clean, slick lines while incorporating elements of the Maroon culture of its former colony (Suriname) and celebrating decorous feminists of color. Quite a feat! Check out Remy Jungerman (first and second images below) who designed the former work and Iris Kensmil (third, fourth and fifth images below), the latter, both of whom are of Surinamese descent. For the names of the women depicted, click here. The artist sent me to the history books to find about some of them.

The show stopper for me, however, was the sculpture of Martin Puryear, who happens to be a black American and who represented the United States in its pavilion. Each of the eight pieces engaged but I found two of them especially compelling: A Column for Sally Hemings, which drives a stake into a pristine Doric column (first photo below), evocative of the entry columns of the building’s Jeffersonian design, and Aso Oke. a lattice like bronze (yes, it’s amazingly made from bronze) interpretation of so-named Nigerian headwear (second photo below).

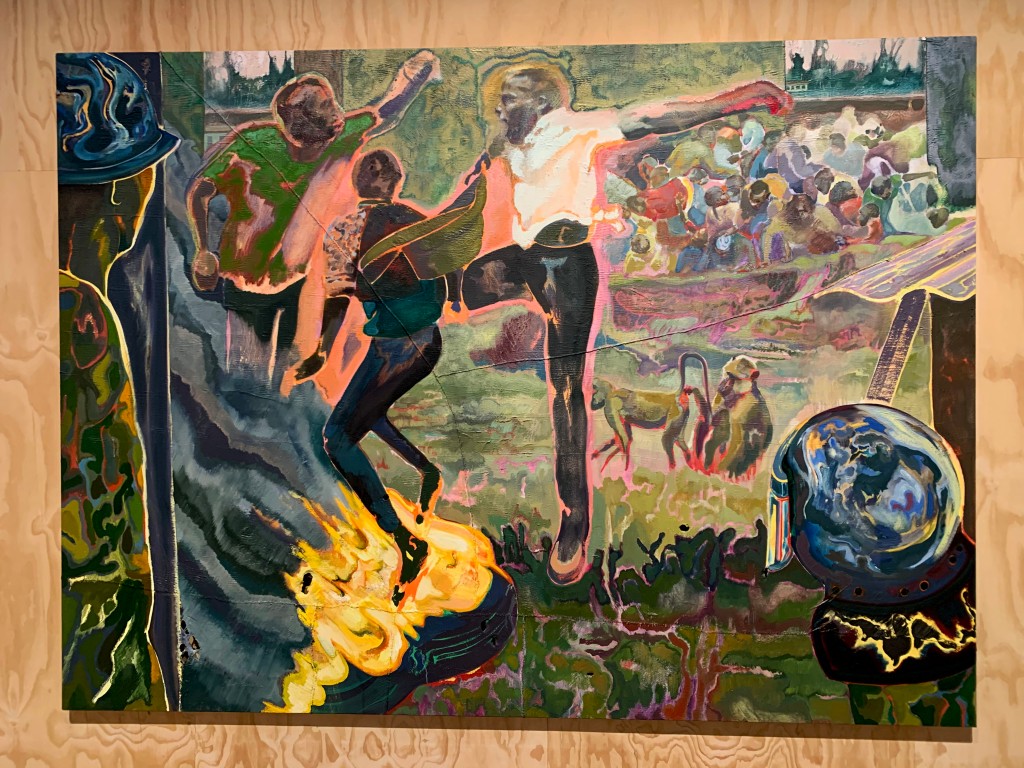

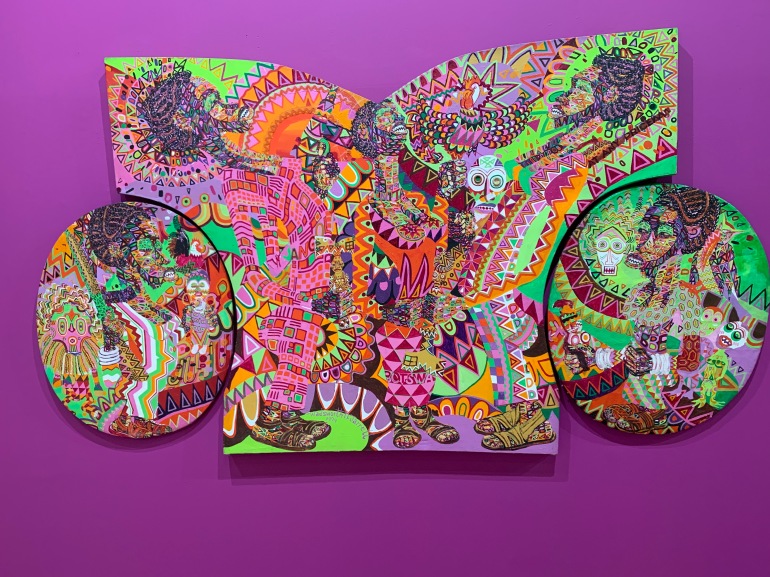

I’ve included some other images that startled, amused, and provoked thought. But, alas, they were few and far between.

Zanele Muholi

Yin Xiuzhan Trojan

Michael Armitage

Michael Armitage

You must be logged in to post a comment.